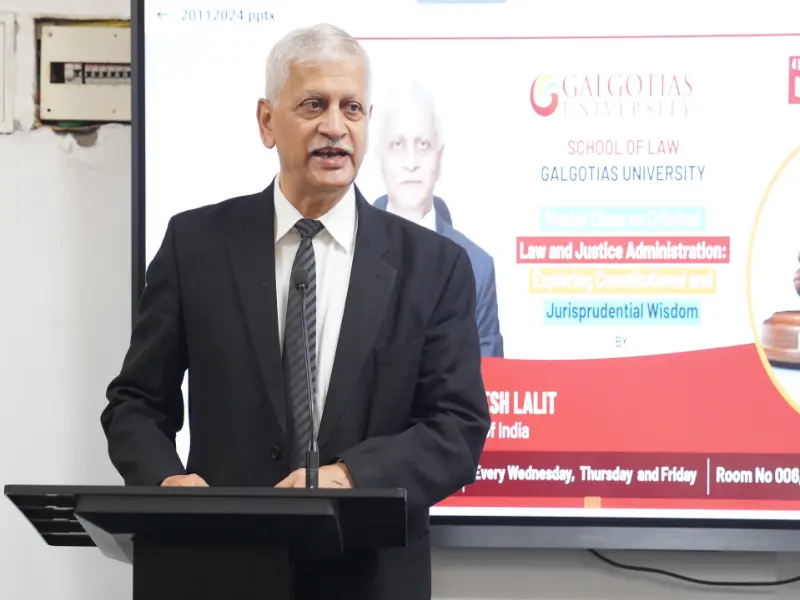

Master Class on Criminal Law and Justice Administration: Exploring Constitutional and Jurisprudential Wisdom

Masterclass by Hon'ble Justice Lalit- Third week

Event Date: 04th - 06th December 2024

DAY 07: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

The seventh day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit’s lecture series was an enlightening session focused on significant aspects of constitutional and criminal law. Justice Lalit began by discussing the power of pardon and its appropriate implementation, emphasizing its critical role in the justice system. He examined the violation of fundamental rights through the landmark A. K. Gopalan Case and explained the concept of “procedure established by law.”

Delving into pivotal cases, he analyzed Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India, addressing delays in death penalty convictions and commutations to life imprisonment, as well as the Triveniben Case, which defined post-conviction responsibilities of courts. Key considerations included delays in mercy petitions, the accused’s mental and physical state, and the implications of High Court appeals reversing acquittals or enhancing sentences.

Justice Lalit discussed solitary confinement through the Sunil Batra Case, emphasizing case-specific guidelines, and addressed the principle of per incuriam in the Parliament Attack Case. He reviewed other notable judgments, including M. C. Mehta v. Union of India, which clarified the non-binding nature of the CBI Manual, and Ajay Kumar Pal v. Union of India, which explored bail grants

The session concluded with discussions on mercy petition codification under Section 472 of BNSS, emphasizing time limits to avoid delays, and the latest CBI v. Thommandru Hannah Vijayalakshmi Case.

The seventh day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit’s lecture series focused on critical discussions regarding the legal aspects of pardon, violations of fundamental rights, and notable case laws shaping Indian jurisprudence.

Justice Lalit began with an in-depth analysis of the pardon power, emphasizing the contexts in which it can be implemented. He highlighted the balancing act between justice and mercy, discussing cases where clemency is warranted due to mitigating factors such as mental health or prolonged delays in executing sentences.

The case of A. K. Gopalan v. State of Madras was revisited to illustrate the violation of fundamental rights and the interpretation of "procedure established by law." He elucidated the implications of this case for individual liberty and procedural fairness, laying the foundation for evolving legal standards.

Next, Justice Lalit discussed Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India, focusing on delays in executing death penalties, which often result in commutation to life imprisonment. This principle was further elaborated through the Triveniben Case, which laid down post- conviction considerations, including delays in mercy petitions, the mental health of the accused, and the reversal or enhancement of sentences by appellate courts.

He also explored the impact of solitary confinement, citing the Sunil Batra Case, and discussed the criteria for determining its appropriateness on a case-by-case basis. Addressing per incuriam decisions, he referenced the Parliament attack case, emphasizing the need for consistent legal interpretations.

Justice Lalit shed light on procedural and constitutional dimensions through significant cases like M. C. Mehta v. Union of India, which clarified that the CBI Manual is not binding or mandatory, and Ajay Kumar Pal v. Union of India, which dealt with bail considerations. He also discussed B. A. Umesh v. Union of India, reflecting on judicial discretion in complex criminal matters.

Special focus was given to Section 472 of the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), which codifies the process for filing mercy petitions in death sentence cases, introducing a fixed timeline to prevent undue delays. He emphasized how this codification ensures fairness and procedural integrity

Justice Lalit concluded the session by analyzing the latest case of CBI v. Thommandru Hannah Vijayalakshmi, underlining its significance in shaping contemporary legal principles.

Through these detailed discussions, Justice Lalit provided the students with a comprehensive understanding of the nuances of mercy petitions, procedural safeguards, and judicial accountability. By bridging theoretical knowledge with real-world case examples, the session enriched the students' grasp of the complexities of Indian legal systems and constitutional mandates. The lecture left the audience with profound insights into how justice is administered while upholding the rule of law and individual rights

Event Outcome- The seventh day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit’s lecture series provided students with an enriched understanding of the complexities of mercy petitions, procedural safeguards, and the balancing act between justice and By discussing landmark cases like A. K. Gopalan, Shatrughan Chauhan, and Sunil Batra, students gained insights into constitutional interpretations, delays in death penalty executions, and the ethical considerations of solitary confinement. Detailed analysis of Section 472 of BNSS and recent judgments like CBI v. Thommandru Hannah Vijayalakshmi equipped students with practical knowledge about evolving legal frameworks. The session inspired critical thinking and a deeper appreciation for judicial processes.

DAY 08: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

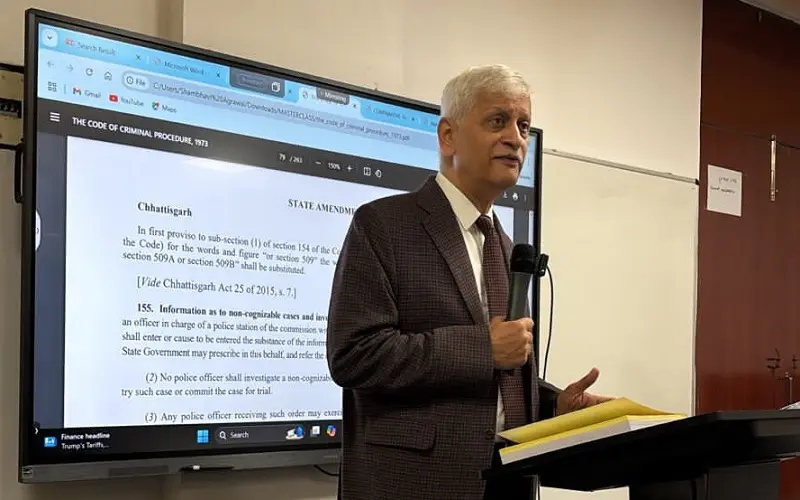

On the eighth day of his lecture series, Former Chief Justice of India Hon’ble Justice U. U. Lalit Sir delved into several important aspects of criminal law, judicial processes, and legislative amendments. He began with an exploration of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2005, highlighting the introduction of anticipatory bail in the 1973 Code, which was previously absent. Justice Lalit then discussed the Maharashtra Amendment Act, 2005, which mandates the presence of the accused in court for anticipatory bail.

He moved on to Section 482 of the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and outlined its relevance. In reference to Sections 65 and 70 of BNSS, he pointed out gaps in addressing acid attacks and vegetative state cases, which were not covered. Justice Lalit also discussed Section 4 of BNSS, detailing the trial of offenses under both BNSS and other laws.

He touched upon the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, addressing conflicts with existing laws and emphasized the K. S. Puttaswamy case, explaining how understanding the dharma of the Constitution applies to the karma of adjudication. The Bhopal Gas Tragedy case was cited as an example of Section 304A of the IPC.

Concluding the lecture, he compared CrPC and BNSS, explained Section 198A of CrPC, discussed the principle of Satyameva Jayate, and illustrated how a judgment is delivered through the Bachchan Singh Case.

Event Report 2: Day Eight of Former Chief Justice U. Lalit’s Lecture Series

The eighth day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit’s lecture series was a deeply insightful session covering various aspects of criminal law, legislative amendments, and judicial principles. The lecture began with an exploration of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2005, particularly the introduction of anticipatory bail. Justice Lalit discussed how anticipatory bail was not part of the old Code and how it was first incorporated into the 1973 Code, marking a significant development in criminal law. He highlighted the evolution of legal provisions, including the Maharashtra Amendment Act, 2005, which stipulates that a person must be present in court to apply for anticipatory bail under Maharashtra’s legislation.

Shifting to the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), Justice Lalit focused on Section 482, discussing its application in various criminal procedures. He then moved to Sections 65 and 70 of BNSS, which outline provisions related to rape and gang rape. He pointed out the gaps in the legislation, specifically noting that acid attacks and situations involving victims in a vegetative state were not addressed in the current provisions. This highlighted the need for further legislative refinement in dealing with emerging forms of violence.

Justice Lalit continued with an analysis of Section 4 of BNSS, which governs the trial of offenses under both the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita and other laws. This section was explained as a crucial part of ensuring justice in complex cases involving multiple legal frameworks. He then turned his attention to the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, discussing its provisions related to children and the conflicts that arise between juvenile laws and adult legal systems, emphasizing the complexities of balancing protection with accountability in the juvenile justice system.

A notable moment in the lecture was when Justice Lalit reflected on the phrase "when you know the dharma of the Constitution, then the karma of the adjudicature is applicable", quoting the K. S. Puttaswamy Case. This concept underscored the profound responsibility of judges in upholding constitutional principles and ensuring justice through their adjudications.

The lecture also delved into the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, focusing on the legal implications following the tragedy, where over 500 people died. Justice Lalit explained how the case was initially charged under Section 304A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, which deals with death due to negligence, and discussed the broader challenges in holding corporations accountable for environmental disasters.

Comparing the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) with BNSS, Justice Lalit discussed the key differences and how BNSS has incorporated some reforms to make the system more accessible and fairer. He highlighted Section 198A of the CrPC, which deals with the prosecution of offenses under Section 498A of the IPC, and explained how BNSS has modified certain provisions to better address issues such as domestic violence.

Moving on, Justice Lalit discussed the concept of Satyameva Jayate, emphasizing its importance as a guiding principle in Indian justice and how it aligns with the constitutional goal of truth and justice.

Finally, Justice Lalit touched upon the procedural aspects of how a judgment is given, drawing on his experience in the landmark Bachchan Singh Case. He discussed the rationale behind the court’s decision-making process, how judges balance legal arguments with the broader principles of justice, and the importance of consistency in delivering decisions.

In conclusion, the lecture provided a thorough examination of critical legal provisions, judicial precedents, and constitutional principles, equipping students with a deeper understanding of India’s legal framework and the evolving challenges in criminal justice.

Event Outcome- The outcome for students from Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit's eighth-day lecture was a deeper understanding of crucial legal concepts, amendments, and judicial reasoning. Students gained valuable insights into the evolution of criminal law, particularly the introduction of anticipatory bail, provisions under the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita, and the impact of landmark cases like the Bhopal Gas Tragedy and Bachchan Singh The lecture enhanced their comprehension of legal intricacies, including the balance between constitutional dharma andadjudicatorykarma.Additionally, students were encouraged to think critically about gaps in current legalframeworksand therole of judgesinshaping justice.

DAY 09: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

On the ninth day of his lecture series, Former Chief Justice of India Hon’ble Justice U. U. Lalit Sir provided an in- depth analysis of various sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNSS). He began by discussing Sections 41A to 53A of CrPC, relating them to the principles established in the D. K. Basu case. Justice Lalit then compared key provisions of CrPC and BNSS, specifically highlighting Section 41C of CrPC and Section 37 of BNSS regarding designated police officers.

He continued by explaining Section 53A of CrPC, which mandates the medical examination of rape suspects, and clarified doubts regarding Section 54A of CrPC, concerning the identification of arrested individuals. Justice Lalit touched upon Section 57 of CrPC, Sections 105A to 105G of CrPC, and Section 144A of CrPC, and discussed Section 153 of CrPC, which deals with the inspection of weights and measures (now repealed).

Further, he compared Section 154 of CrPC and Section 173 of BNSS, addressing how police information in cognizable cases is handled. Justice Lalit also discussed Section 197 of CrPC, which pertains to the prosecution of judges and public servants, critiquing its colonial origins.

In a lighter moment, he shared a humorous anecdote about Justice Ruma Pal's strict policy on gadgets in courtrooms. The lecture concluded with a discussion of the A. R. Antulay case and Section 218 of BNSS.

Event Report 2: Day Nine of Former Chief Justice of India Hon’ble Justice U. Lalit's Lecture Series

On the ninth day of his insightful lecture series, Former Chief Justice of India Hon’ble Justice U. U. Lalit continued his in-depth exploration of criminal law and legal reforms. The focus of the session was on significant sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNSS), as well as their practical implications in modern legal contexts.

Justice Lalit began by discussing Sections 41A to 53A of the CrPC, which are deeply influenced by the D. K. Basu case. This landmark case had emphasized the need for safeguards against custodial violence and established the requirement for police to inform detainees about their rights. The provisions mentioned in these sections, particularly

concerning arrest and detention procedures, are designed to protect individual rights and prevent abuse of power by law enforcement.

A significant portion of the lecture was dedicated to comparing CrPC and BNSS, drawing attention to their similarities and differences. Justice Lalit highlighted Section 41C of CrPC and Section 37 of BNSS, both of which deal with the role of designated police officers. These provisions outline the authority of police officers in specific circumstances, ensuring that arrests and detentions are conducted under appropriate legal frameworks.

He also discussed Section 38 of BNSS, emphasizing its implications on police procedures and the legal framework surrounding arrest and detention. In the context of Section 53A of CrPC, Justice Lalit explained the procedure for the medical examination of a person accused of rape by a medical practitioner. This section plays a crucial role in preserving the integrity of the investigation and ensuring that the rights of the accused are respected.

Justice Lalit then cleared doubts raised by students regarding various sections of both the CrPC and BNSS. One such discussion focused on Section 54A of CrPC, which mandates the identification of a person arrested. He also elaborated on Section 57 of CrPC, which sets out the time limits within which an arrested person must be brought before a magistrate.

Moving on, Justice Lalit explored Sections 105A to 105G of CrPC, dealing with the prevention of offences and security proceedings. He also discussed Section 144A of CrPC, which relates to the issue of public disturbance and the role of authorities in controlling such situations.

The session also touched upon Section 153 of CrPC, dealing with the inspection of weights and measures, which was later repealed. This provision highlighted the evolving nature of the legal system, adapting to new societal needs and technologies. Justice Lalit then compared Section 154 of CrPC and Section 173 of BNSS, both of which pertain to the filing of information in cognizable cases. He provided detailed explanations of Section 193 of BNSS and Section 173 of CrPC, which mandate the report of the police officer upon completing the investigation.

He also discussed Section 186 of CrPC, which empowers the High Court to decide, in cases of doubt, the appropriate district for inquiry or trial. Section 190 of CrPC and Section 210 of BNSS, which deal with cognizable offenses by magistrates, were also examined in depth.

A particularly interesting segment of the lecture involved Section 197 of CrPC, which addresses the prosecution of judges and public servants. Justice Lalit critiqued this colonial-era concept, questioning its relevance in today’s democratic society and highlighting the need for reform.

The lecture concluded with a humorous anecdote about Justice Ruma Pal’s strict “no gadgets in the courtroom” policy, shedding light on the challenges posed by modern technology in courtrooms. Finally, Justice Lalit discussed the A. R. Antulay case and its connection to Section 218 of BNSS, reflecting on its significance in the context of legal reforms.

Overall, the lecture was a comprehensive examination of critical legal provisions, offering valuable insights into the evolution of criminal law and its application in contemporary India.

Event Outcome-The students gained a deeper understanding of critical legal provisions and their practical implications through Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit's They were able to grasp the nuances of both the CrPC and BNSS, especially regarding arrest procedures, the protection of individual rights, and the evolving nature of legal reforms. The comparison between the two codes provided students with clarity on how legal frameworks adapt to societal needs. Additionally, the case studies and discussions on landmark judgments helped students apply theoretical knowledge to real- life scenarios, fostering a comprehensive understanding of criminal law.

Masterclass by Hon'ble Justice Lalit- Second week

Event Date: 27th - 29th November 2024

DAY 04: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

The fourth day of the lecture series by former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit delved into a detailed comparison between the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), highlighting their similarities, amendments, and practical implications. Justice Lalit began with IPC Section 96, addressing dacoity and murder, before comparing provisions related to food adulteration in the IPC and BNS. He noted how state amendments to the IPC had been streamlined in the BNS and emphasized how the BNS prioritizes victims' lives more than the IPC.

During the discourse, sir transitioned to the topic of adulteration of food, comparing provisions under the BNS to those in the IPC. Justice Lalit pointed out that while states had amended the IPC over the years to address region-specific concerns, such amendments were removed in the BNS, standardizing its application across the country. He emphasized how the BNS prioritizes the life and safety of victims more explicitly than the IPC, signaling a shift towards victim-centered justice.

He discussed new inclusions in the BNS, such as provisions for hijacking, hostage situations, and air jacking—added to the IPC after the Kandahar tragedy. He highlighted the introduction of community service for minor offenses, while critiquing the lack of clarity regarding its nature and duration. Justice Lalit compared the advantages and disadvantages of the BNS, praising the removal of sedition and reducedpenalties for self- reporting, while questioning the necessity of a new act for minor updates.

Lastly, he revisited the tragic Shatrughna Baban Meshram v. State of Maharashtra (2013) case to discuss IPC's rape provisions, concluding with BNS’s core intent: removing sedition and revising key legal principles.

A significant portion of the lecture was dedicated to the expanded scope of kidnapping and abduction laws in the BNS. Justice Lalit explained how provisions now include modern crimes such as hijacking, hostage-taking, and airjacking—issues that gained attention in the aftermath of the Kandahar Tragedy, where an Indian Airlines flight was hijacked in 1999. He noted that these additions ensure that the law remains relevant in addressing contemporary forms of crime.

One notable reform discussed was the introduction of community service as a punishment in the BNS for petty offenses, such as public misconduct by intoxicated individuals or minor defamation cases. While Justice Lalit acknowledged the potential benefits of this reform, he criticized its lack of specificity regarding the type and duration of community service to be imposed, which might limit its effectiveness.

Justice Lalit further elaborated on the advantages and disadvantages of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita. Among the advantages, he highlighted the removal of sedition provisions, a move he lauded for fostering greater freedom of expression and allowing citizens to criticize the government without fear. He also praised the BNS’s efforts to promote good citizenship by reducing penalties for individuals who voluntarily surrender or report themselves in cases such as road accidents. However, he expressed skepticism about the necessity of introducing the BNS as a separate act, suggesting that its changes could have been incorporated into the IPC through amendments, given that many of the revisions were minor.

Justice Lalit concluded his lecture by discussing a poignant case he presided over, Shatrughna Baban Meshram v. State of Maharashtra (2013), in which a two-and-a-half- year-old girl was brutally raped and murdered. He reviewed the provisions of the IPC concerning rape at the time, emphasizing the severity of the crime and the judiciary's responsibility to deliver justice in such cases.

In his closing remarks, Justice Lalit summarized the core objectives of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, which include removing outdated provisions like sedition and adapting certain principles to reflect contemporary societalneeds.Thelectureprovidedacomprehensive exploration of the evolving legal landscape, offering students criticalinsightsintothereformsandchallengesshapingIndia’sjudicialsystem.

Event Outcome- The students gained a deeper understanding of the evolution of India’s criminal justice system, particularly the distinctions between the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS). Justice Lalit's comparative analysis highlighted the practical implications of legislative reforms, such as expanded definitions

for crimes like kidnapping and the introduction of community service for minor offenses. His discussion on victim-centred justice and the removal of sedition provisions broadened their perspective on constitutional freedoms and modern governance. The exploration of landmark cases, including the Shatrughna Baban Meshram case, offered real-world applications of these laws, enhancing their critical thinking and legal knowledge.

DAY 05: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

The fifth day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit’s lecture series focused on the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and its relevance to civil liberties. He explained provisions regarding sentences in default of fines and highlighted the sentencing powers of High Courts and Sessions Judges. Justice Lalit also shared rare judicial journeys, such as Justice K. N. Wanchoo’s rise to Chief Justice without a law degree and other inspiring anecdotes.

He emphasized the constitutional significance of A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, the first case before a constitutional bench, and Advocate M. K. Nambyar’s pivotal role in shaping constitutional law. Moving to the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), he detailed Section 167, focusing on judicial custody, bail provisions, and their challenges, criticizing the disparity faced by those unable to furnish bail.

Fifth day of the lecture was focused on the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and its intersections with civil liberties, judicial processes, and notable legal precedents. The session offered a thorough exploration of the BNSS and relevant provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), supplemented by historical insights and landmark cases.

Justice Lalit began by discussing sentences of imprisonment in default of a fine under the BNSS and the scope of sentences that High Courts and Sessions Judges may impose. He clarified that while Sessions Judges are bound by statutory limits, High Courts have the authority to pass any sentence authorized by law, emphasizing their pivotal role in the justice system.

In a fascinating detour, Justice Lalit introduced Justice K. N. Wanchoo, an Indian Civil Services (ICS) officer who rose through the ranks to become the 10th Chief Justice of India despite not holding a formal law degree. He also mentioned Justices Palekar and Pant, who began their careers at lower levels of the judiciary before ascending to the Supreme Court. A particularly unique anecdote highlighted Justice Bela Trivedi, who served as a judge in a Civil Court simultaneously with her father.

Justice Lalit then linked the BNSS to civil liberty, underscoring its foundational relevance in safeguarding individual rights. This was followed by an engaging discussion on the landmark case of A. K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, the first trial before the Supreme Court’s Constitutional Bench. The case established M. K. Nambyar as a preeminent constitutional lawyer through his compelling arguments on due process and personal liberty.

The focus shifted to the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), particularly Section 167, which governs procedures when investigations cannot be completed within 24 hours. Justice Lalit detailed how the nearest magistrate oversees the process and the provision for judicial custody. He explained the extension periods: 60 days for offenses punishable by imprisonment under 10 years and 90 days for more severe offenses, including life imprisonment and death penalty cases. If investigations remain incomplete, the accused is entitled to statutory or default bail, contingent on the ability to furnish bail. However, he criticized this provision for disadvantaging economically marginalized individuals who cannot afford bail.

Justice Lalit discussed custodial violence through the lens of D. K. Basu v. State of West Bengal, emphasizing the Supreme Court's guidelines to prevent third-degree interrogation practices. He also cited Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar, a case that underscored the unconstitutionality of delays in trials and the importance of timely justice in upholding the rule of law.

Through a chart, he explained the procedural steps for filing an application, simplifying the complexities of judicial procedures. He discussed the Sanjay Dutt case in relation to Section 167 and delved into Uday Mohanlal Acharya v. State of Maharashtra, which addressed bail cancellation based on the accused’s conduct. Notably, this ruling marked a shift away from precedents set by the Sanjay Dutt case.

Justice Lalit highlighted landmark cases like D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (custodial violence) and Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (trial delays). Using charts, he explained procedural intricacies and analyzed cases such as Sanjay Dutt and Uday Mohanlal Acharya concerning bail. The lecture concluded with insights on the Sampat Kumar case, providing students a comprehensive understanding of justice, procedure, and civil liberties.

Finally, Justice Lalit concluded by discussing the Sampat Kumar case, which was later declared “per incuriam” by the Andhra Pradesh High Court, highlighting its deviation from established legal principles.

The lecture provided students with a profound understanding of civil liberties, procedural safeguards, and the evolving dynamics of India’s judicial system, enriched by Justice Lalit’s expertise and real-world case studies.

Event Outcome - The students gained a comprehensive understanding of critical legal concepts, particularly the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and CrPC procedures. They learned about the importance of civil liberties in the judicial system and the authority of High Courts and Sessions Judges in sentencing. The analysis of landmark cases, such as D. K. Basu and Hussainara Khatoon, highlighted the significance of timely justice and the protection of individual rights. Furthermore, students developed a deeper understanding of bail procedures and judicial accountability, equipping them with practical insights into real-world legal practices and procedural law.

DAY 06: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

The sixth day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit’s enlightening lecture series continued to delve into significant aspects of India’s criminal justice system, focusing on provisions in the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC). Justice Lalit combined theoretical understanding with practical applications, enhancing the students’ comprehension of legal principles and procedures.

The session began with a recap of the previous day’s lecture, revisiting Section 167 of the CrPC and its emphasis on judicial custody and statutory bail. Justice Lalit reiterated the paramount importance of personal liberty, stating that it is sacrosanct and must be upheld unless explicitly restricted by due process. This set the tone for a nuanced discussion on the balance between liberty and law enforcement. Addressing student doubts on Section 154 of the CrPC, he linked it to the Lalita Kumari Case and briefly touched upon Advocate Manohar Lal Sharma’s active legal career and the Nupur Talwar Case. He explained Section 472 of BNSS, outlining the process for filing a mercy petition in death sentence cases, and covered sections 473 to 477.

He then discussed the case of Achpal Alias Ramswaroop & Anr. v. State of Rajasthan, emphasizing that granting bail on merit is crucial and must not be confused with other

forms of bail, such as statutory bail. This was followed by an analysis of the Anupam Kulkarni Case, where he illustrated the application of judicial discretion in the context of bail and its far-reaching implications for an accused’s liberty.

Justice Lalit transitioned into a critical evaluation of Section 187 of the BNSS, pointing out its apparent contradiction to the broader principle of “Nagrik Suraksha” or citizen protection. This section became a springboard for exploring the delicate interplay between maintaining public order and protecting individual freedoms under the law.

A lively interactive session ensued, where students posed questions regarding Section 154 of the CrPC, which deals with the recording of First Information Reports (FIRs). Justice Lalit linked this to the Lalita Kumari Case, a landmark judgment that made the registration of FIRs mandatory for cognizable offenses. He praised Adv. Manohar Lal Sharma for his active engagement in legal reforms and briefly touched upon the Nupur Talwar case, providing insights into the complexities of criminal investigations.

The focus then shifted to Section 472 of the BNSS, which addresses the filing of mercy petitions in cases of death sentences. Justice Lalit explained the procedural specifics, noting that the convict’s legal heir or relative can file the petition within 30 days after being informed of the dismissal of an appeal. This section reflected BNSS’s attempt to streamline processes while preserving human dignity.

Justice Lalit also reviewed the Kihoto Holohan Case, which dealt with judicial review and constitutional amendments, offering students a broader understanding of the judiciary’s evolving role. He elaborated on Sections 473 to 477 of the BNSS, highlighting their procedural nuances.

A comparative analysis of provisions in the CrPC and BNSS followed. For instance, he pointed out the removal of Section 144A of the CrPC, which deemed mass drills and parades as obnoxious, signaling BNSS’s streamlined approach. Justice Lalit compared provisions in the CrPC and BNSS, such as the removal of CrPC Section 144A on mass drills.

The lecture concluded with a discussion on provisions for prosecuting judges and public servants, emphasizing accountability within the justice system. Justice Lalit’s meticulous explanations and practical examples enriched the students’ understanding of the evolving legal landscape. Concluding with discussions on the prosecution of judges and public servants, the lecture provided a holistic view of procedural law and constitutional principles.

Event Outcome- The sixth day of the lecture series provided students with profound insights into critical legal provisions and their real-world implications. They gained a deeper understanding of the balance between individual liberty and legal processes,

particularly through discussions on statutory bail, mercy petitions, and prosecuting public servants. The analysis of landmark cases such as Achpal Alias Ramswaroop, Lalita Kumari, and Kihoto Holohan enhanced their ability to connect legal theory with practice. Students also appreciated the comparative analysis of CrPC and BNSS provisions, equipping them with knowledge of evolving legal frameworks. This session fostered analytical thinking and a nuanced approach to justice.

Event Date: 20th - 22nd November 2024

DAY 01: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

The inaugural session of the guest lecture series by former Chief Justice of India, U. U. Lalit, was held today, focusing on the evolution and impact of key legislations addressing terrorism and organized crime. Justice Lalit began by explaining how terrorism in Punjab necessitated the creation of special laws that empowered the police with exceptional rights, including recording confessions and implementing drastic procedural changes.

He provided an in-depth analysis of the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA) and the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999 (MCOCA), discussing their substantive, procedural, and evidentiary aspects. Drawing from real-world applications, he shared insights through the notable case of the "J J Shootout at Bombay," illustrating the operational scope of these laws.

Justice Lalit highlighted how sections of the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita related to organized crimes and terrorist acts have been derived from TADA and MCOCA, emphasizing their influence on contemporary legal frameworks. Concluding his lecture, he addressed the contentious issue of sedition, drawing references from the Indian Penal Code to discuss its historical and present-day implications. The session offered a comprehensive perspective on the evolution of India's legal responses to crime and security challenges.

The inaugural session of the much-anticipated guest lecture series by former Chief Justice of India, U. U. Lalit, took place today, setting a compelling tone for the series. Justice Lalit, a renowned legal luminary, captivated the audience with his incisive analysis of India’s legislative framework addressing terrorism, organized crime, and sedition.

Justice Lalit began by highlighting the historical context that shaped the formulation of special terrorism laws in India. He discussed how the rise of terrorist activities in Punjab during the 1980s necessitated drastic procedural changes to address the unique challenges posed by terrorism. These changes led to the enactment of laws granting significant powers to law enforcement agencies, including the authority to record confessions. Such measures marked a sharp departure from conventional legal procedures, as they sought to empower the police and judiciary to combat terrorism more effectively.

A significant portion of the lecture was devoted to explaining the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA) and the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999 (MCOCA). Justice Lalit delved into the substantive, procedural, and evidentiary aspects of these landmark legislations. He emphasized how these laws were specifically tailored to address terrorism and organized crime, focusing on their unique provisions, such as admissibility of confessions made to police officers and stringent bail conditions. Justice Lalit illustrated the practical application of these laws through the infamous “J J Shootout at Bombay” case, providing real-world insights into their implementation.

Connecting the past with the present, Justice Lalit explained how the newly proposed Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita (BNS) draws inspiration from TADA and MCOCA. He noted that sections of the BNS dealing with organized crime and terrorism have evolved by incorporating key principles from these earlier legislations. This linkage underscores the continuity in India’s legislative approach to tackling organized crime and terrorism while ensuring its alignment with constitutional values and human rights.

In the concluding segment, Justice Lalit addressed the topic of sedition, a subject of intense debate in contemporary India. He referenced Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which deals with sedition, and its intersection with Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to free speech. Justice Lalit emphasized the delicate balance between ensuring national security and protecting individual freedoms, a challenge that lawmakers and the judiciary continue to navigate.

The first day of the lecture series was both informative and thought-provoking, offering participants a nuanced understanding of India’s evolving legal landscape. Justice Lalit’s ability to contextualize complex legal principles within real-life scenarios enriched the discussion and set the stage for the upcoming sessions. The audience left with a deeper appreciation for the role of law in addressing contemporary challenges while safeguarding democratic values.

DAY 02: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

The second day of the lecture series by former Chief Justice of India, U. U. Lalit, focused on sedition and landmark legal cases that have shaped its interpretation. Justice Lalit analyzed three key cases, beginning with Kedarnath Singh v. State of Bihar, where he discussed Singh’s advocacy for armed rebellion and hate speech against the government under Section 124A of the IPC. He emphasized the balance between freedom of speech under Article 19(1)(a) and the inherent right to criticize the government. The second case, Vinod Dua v. Union of India, highlighted the sedition charges against journalist Vinod Dua for raising concerns about the plight of migrants during Covid-19 on The Vinod Dua Show – Curtain Raiser. Lastly, he discussed Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab, related to the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA), commending Advocate V. M. Tarkunde’s unique approach.

Justice Lalit celebrated the judiciary’s progress in removing sedition and refining laws like TADA and MCOCA to include organized crime and terrorism. He concluded with an analysis of the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case (State v. Nalini), presided over by Justices Thomas J. and Quadri, offering profound insights into India's legal evolution.

The second day of the guest lecture series by former Chief Justice of India, U. U. Lalit, centered around the complex and evolving nature of sedition laws and their interplay with anti-terrorism legislation in India. Justice Lalit provided a thorough analysis of significant legal milestones, beginning with a discussion on sedition. He explored three landmark cases that have shaped public and judicial discourse on the subject.

The first case, Kedarnath Singh v. State of Bihar, highlighted the tensions between free speech and state sovereignty. Justice Lalit explained how Kedarnath Singh, through his speeches, advocated armed rebellion against the government and engaged in hate speech, actions that invoked Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The case became a touchstone for interpreting the limits of sedition, with the Supreme Court affirming the constitutional validity of Section 124A but emphasizing that only speech inciting violence or public disorder could be punished under it. Justice Lalit juxtaposed this with Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech, reiterating the inherent right of individuals to criticize the government within reasonable boundaries.

The second case discussed was Vinod Dua v. Union of India, which brought sedition laws into the spotlight during the COVID-19 pandemic. Justice Lalit recounted how veteran journalist Vinod Dua expressed concerns over the government’s handling of the migrant crisis during his show, The Vinod Dua Show – Curtain Raiser. Although his criticism aimed at raising awareness, it led to sedition charges, sparking a debate on the misuse of sedition laws to stifle dissent. Justice Lalit emphasized the judiciary’s role in protecting freedom of speech and ensuring that sedition laws are not weaponized against legitimate critique.

The third case, Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab, related to the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA). Justice Lalit highlighted the legal acumen of advocate V. M. Tarkunde, whose unique approach to defending the accused in this case demonstrated the challenges of balancing civil liberties with national security concerns. He noted that this case underscored the importance of procedural fairness, even in matters involving terrorism.

Justice Lalit also discussed the judiciary’s pivotal role in the removal of sedition laws and the integration of organized crime and terrorism provisions from TADA and MCOCA into more comprehensive frameworks. He described this development as a landmark achievement that upheld constitutional values while addressing emerging threats.

In conclusion, Justice Lalit delved into the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case (State v. Nalini), a pivotal trial presided over by Justices Thomas J. and Quadri. He reflected on the legal intricacies and societal impact of the case, emphasizing the judiciary’s responsibility in high-profile and sensitive matters.

The session offered a profound exploration of how India’slegalsystem continues to evolve in addressing the balance between individual freedoms, state security, and the pursuit of justice, leaving attendees with a deeper understanding of the challenges and achievements within the judiciary.

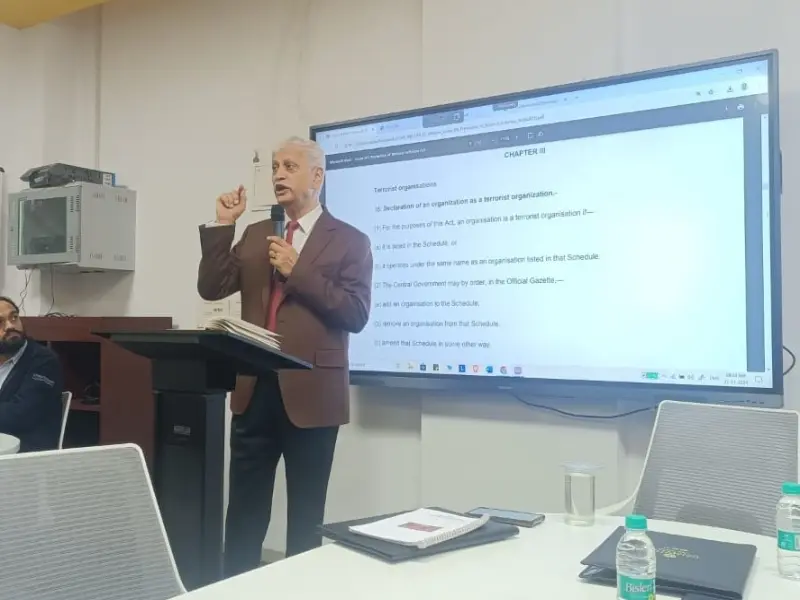

DAY 03: MASTER CLASS BY JUSTICE U. U. LALIT

On the third day of Former Chief Justice U. U. Lalit's lecture series, he discussed significant legal reforms aimed at combating terrorism, financial crimes, and improving India's penal system. He began with the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA), explaining its provisions after the repeal of the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA). POTA introduced new sections criminalizing witness intimidation and fundraising for terrorist organizations, and established a list of designated terrorist organizations. The Act, however, did not address co-accused liability like TADA and directed appeals to the High Court. Justice Lalit also covered the National Investigation Agency (NIA) Act, 2008, and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), noting UAPA's provisions on company liability and its role in tackling terrorism. He then discussed the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA), highlighting its role in preventing money laundering and confiscating assets linked to such crimes. Lastly, Justice Lalit reflected on the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita, emphasizing its improvements, such as extending life imprisonment to the natural lifespan of prisoners and gender-neutral provisions in child trafficking laws. He critiqued the continued gender-specific language in rape laws, calling it a step backward in modern society.

The third day of the guest lecture series by former Chief Justice of India, U. U. Lalit, focused on several crucial pieces of legislation that have shaped India’s approach to counter-terrorism, financial crimes, and evolving penal reforms. Justice Lalit began by discussing the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA), which was introduced after the repeal of the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA). Justice Lalit explained that POTA incorporated several new provisions, such as making the act of threatening a witness a punishable offense. He also noted that Chapter 3 of the act was dedicated to Terrorist Organizations, defining and listing organizations involved in terrorist activities. Notably, POTA criminalized fundraising for terrorist groups, reflecting the growing concern over the financial support for terrorism. A significant difference from TADA was that POTA did not address the liability of co-accused individuals. He also highlighted the procedural change that shifted appeals from the Supreme Court to the High Court under POTA. Despite its controversial nature, Parliament repealed POTA in 2004, marking the end of its legal influence.

Justice Lalit then moved on to the National Investigation Agency (NIA) Act, 2008, explaining its role in strengthening the investigation and prosecution of terror-related cases. The NIA Act was pivotal in establishing the National Investigation Agency, which centralized anti-terror investigations in India and provided a specialized agency to handle cases involving national security. This was seen as a strategic move to enhance the coordination and effectiveness of counter-terrorism efforts across the country.

Next, Justice Lalit discussed the Unlawful Activities(Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), a law that has been in force since its inception, dealing with terrorist acts and the unlawful activities associated with them. He pointed out that UAPA not only targets individuals involved in terrorist activities but also extends to corporate entities, making them liable for offenses, including vicarious liability. The Act also defines the formation of a tribunal to adjudicate matters related to unlawful activities, which ensures a more organized and legal approach to national security.

The lecture also covered the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA), which focuses on tackling money laundering activities and the financial operations tied to criminal enterprises, including terrorism. Justice Lalit highlighted that PMLA is designed to prevent the laundering of money through the confiscation of assets linked to criminal activity. The act also mandates stringent reporting and investigative mechanisms to prevent money laundering from occurring in India.

In the final segment of his lecture, Justice Lalit focused on the reforms introduced through the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita, a proposed revision of the Indian Penal Code. He emphasized how the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita has incorporated lessons learned from past legal experiences, with significant improvements made in the punishment for certain crimes. A notable amendment was the extension of life imprisonment from 14 years to a prisoner’s natural life, reflecting a shift toward more substantial punishment for serious offenses. He referenced the Masalti Judgement, delivered by Justice Vivian Bose, which addressed issues of punishment for murder under the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita, often referred to as the "Masalti Law." He also pointed out key differences between the punishments under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita, underscoring the need for reforms in penal policies.

Justice Lalit further discussed the evolving nature of laws relating to child trafficking, particularly in cases involving the buying and selling of children for prostitution. The Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita made these laws gender-neutral, addressing both boys and girls, a significant shift from previous laws that were primarily focused on girls. Finally, he touched on the issue of rape laws, criticizing the continued use of gender-specific language in defining the offense of rape, which only mentions females as victims. He called for reforms to make these provisions more inclusive, reflecting contemporary societal norms.

The lecture offered a profound analysis of how India’s legal system has evolved to address pressing issues such as terrorism, financial crimes, and gender equality in the justice system. Justice Lalit’s insights into the legal reforms in India were a valuable resource for understanding the complexities of criminal law and its ongoing development.

Event Outcome- The students gained valuable insights into India's evolving legal framework, particularly in counter-terrorism, financial crimes, and penal reforms. Justice Lalit's in-depth analysis of laws like POTA, UAPA, and PMLA enriched their understanding of national security and the judicial response to emerging threats. The discussion on the Bhartiya Nyay Sanhita and its improvements provided a critical perspective on legal reforms, emphasizing the need for inclusivity and the adaptation of laws to contemporary issues. The lecture also sparked discussions on the balance between individual rights and national security, offering students a broader, nuanced view of the legal landscape.

Mentor Name – Hon’ble Justice U U Lalit, Former Chief Justice of India

Department Name – School of Law